The Baxandall Visiting Fellowship

Professor Krista Kesselring, Dalhousie University, Canada

Professor Krista Kesselring visited Robinson as a Baxandall Fellow in the Lent and Easter terms of 2025. Usually based in the History Department at Dalhousie University in Canada, she teaches Early Modern English History. Her research typically examines how people used law to mediate changing social and political relationships over time; much of her recent work has focused on the Court of Star Chamber. The new research that was the centre of her work at Robinson – and the subject of her public Baxandall Lecture, given in March 2025 – drew on Star Chamber records to examine the role of the jury in English witch trials.

at Dalhousie University in Canada, she teaches Early Modern English History. Her research typically examines how people used law to mediate changing social and political relationships over time; much of her recent work has focused on the Court of Star Chamber. The new research that was the centre of her work at Robinson – and the subject of her public Baxandall Lecture, given in March 2025 – drew on Star Chamber records to examine the role of the jury in English witch trials.

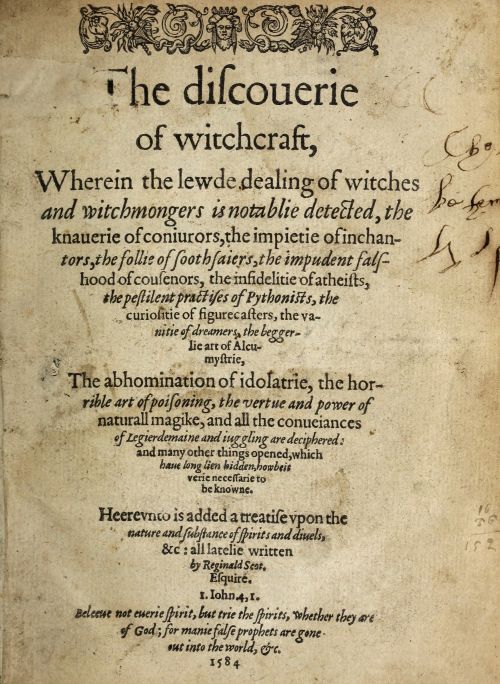

As noted in my Baxandall Lecture The Jury, the Witch and the Shadow of Doubt: Witchcraft on Trial in Early Modern England, even though hundreds of people – mostly women – were executed for crimes related to witchcraft in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, hundreds more suspects went free. Juries discharged or acquitted a high proportion of people accused of using witchcraft to cause harm, even at the peak of the so-called 'witch hunting’ era in England’s history. How can we explain this high acquittal rate and what might we learn from it? Historians of witchcraft have previously pointed to peculiarities of proof and procedure to explain England’s distinctive patterns of prosecution: the absence of judicial torture and inquisitorial process helped keep numbers of executions lower in England than in some other countries. My work examined the role of another distinctive element of English criminal procedure: the jury, and more particularly, the grand jury.

I shared my findings on a case heard in the Court of Star Chamber against a group of grand jurors accused of perjury for their refusal to indict a woman accused of murder-by-witchcraft. The unusually well documented trial of the jurors allowed a close study of the decision-making involved in bringing suspected witches to trial and in the common outcome of letting so many go free. In this case, I was able to follow the accusations of witchcraft and jury malfeasance from their emergence in rural Buckinghamshire through to the central courts at Westminster and examine them in their broader political, religious, and legal contexts. In the end, neither the woman accused of witchcraft nor the jurors who opted to believe her faced punishment. The case study shows that restraint, doubt, and decency could be shown not only by learned, elite scholars and judges but also by community members of modest or middling means, either individually as witnesses or collectively as jurors. This highlights the presence and significance of what we might characterize as a rough-and-ready ‘reasonable doubt’, even in the midst of fears and tensions that might push some people to deadly certainties.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Dr Leigh Baxandall for the generous gift that made this fellowship possible, and also the entire Robinson community. I met so many brilliant and welcoming Fellows, staff, and students at Robinson. I had the time to do a fair amount of research and to write several new articles, now submitted for publication, but I also enjoyed many chances to talk with other members of the College and the University beyond. In addition to giving my talk about witchcraft on trial, I led a workshop for a group of History PhD students and participated in an event hosted by Robinson’s History Society. I also attended many seminars and lectures. I have been a very lucky beneficiary of this support and will remember my time at Robinson as a Baxandall Fellow with great fondness and gratitude.